Metronomes in Human Experience

What defines the present moment and characterises our passage through it? Not the ticking of the clock surely. But in a world defined by constant change how does any creature great or small differentiate one moment from the next, separating out parcels from undifferentiated duration.

Metronomes help. The beat of a drum, the beat of my heart, the great throb of the ocean on the shore. The day, rolling across us again and again.

What are our most familiar metronomes and how do they situate us?

The Year

Top notes: spring flowers and breeding, autumn leaves

Heart notes: summer sun, winter snow

Bass notes: the steady motion of the stars, the equinoxes

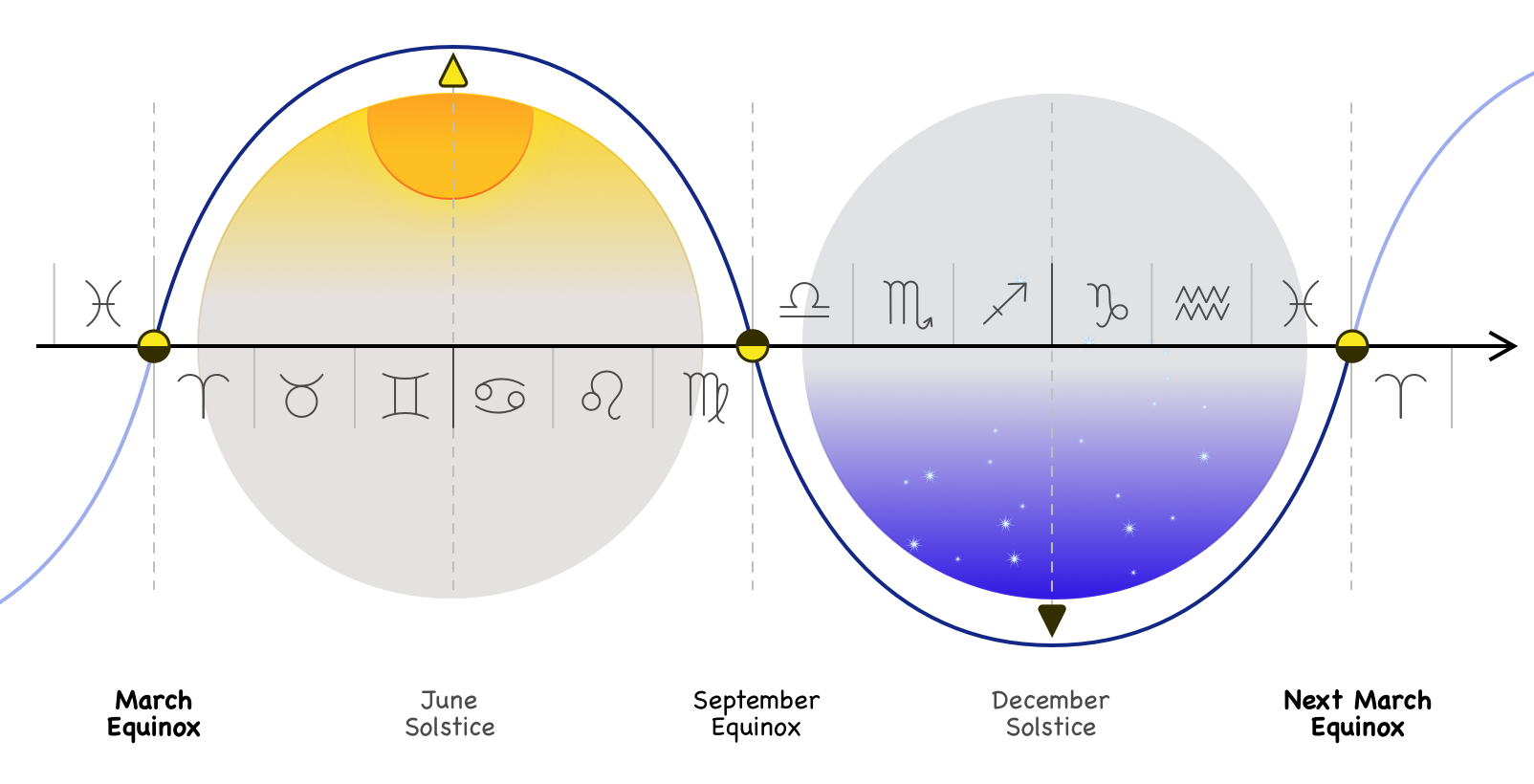

An age unto itself! No doubt the longest time that many animals learn to experience. And perhaps a late arrival to evolutionary history, the year grows louder as we climb ashore and start to brave the North and South. A late arrival to human history as well, our beginnings in the tropics no doubt sheltered us from its worst extremes. Outside the tropics the year reinforces the lessons of the day: binary states, temperature extremes, oscillating back and forth. And the two halves of the year characterized by one kind of change or another– waxing and waning of seasons. The our corners of the year and the four seasons are no anthropomorphic imposition– they are placed at the two extremes, the solstices and at the two moments of fastest change, the equinoxes.

But this is everywhere apparent– because if humans had invented the year, how did nature learn to dress itself in such different fashions? Not by copying our flamboyant displays I’m sure.

Top notes: lunar flowers, lunar insects, lunar corals

Heart notes: the visual spectacle, braving the day and disrupting night

Base notes: the great blanket of the ocean rising and falling in a double lockstep with little luna

The year has a quiet little cousin, Luna. It bridges the great expanse between year and day. Despite being gentler in its influence it mimics the four states, bright and dark, waxing and waning. It fits twelve times in the year and thereby teaches us a great and elegant number. And there are three fours in twelve! What significance has that, do you suppose?

The passage of the moon is quite subtle, but despite its lack of fire we feel its influence upon us, warping and dividing the day into tides, bringing light into the night– a divine and mysterious imposition! And the keen and sensitive eye will see its followers everywhere about– in poor moon-addled moths or menstrual cycles.

And then comes the day. Ah the day! It is impossible to imagine a more perfect span of time. Enough to dream and dance and eat and talk and dream again! What a difference a day makes. In a day you can plan a whole adventure, a feast, a ball– and carry it out as well, bring it all to fruition, gather friends and family and strangers for some great undertaking, some great experience! And then– perhaps by luna’s light– to bed to dream and ready yourself for another. And another and another! Thirty times, almost, until the moon shows the same face– many hundreds– who really knows how many– many hundreds of days until the same flowers will return, the same birds will tell you– and then again and again and again and again, by their hundreds and their thousands they march by. Uncountably many, an inconceivable array, and each one perfect and complete, bracketed by night, lit by the one true God, that unfailing fire-bringer, life-bringer, feeder of plants of warmer of skin and breath!

What a thing is a day. What a marvellous thing.

And it to has its waxing and its waning, dusk and dawn– those still incomparable beauties, those beauties that define beauty, against which all beauty tries and fails.

Top notes: all life, responsive and reactive and aware

Heart notes: the sun the clouds the sky

Bass notes: circadian rhythms, the deep subconscious pulse

What else on that scale? What other rhythms direct us? The stars precede over thousands of years, a slow drift that modulates the sky. The wandering stars and comets go their way. Meteorites periodically light up the sky and earthquakes and hurricanes come and disturb our days from time to time.

But nothing has the beat of those three. They divide up our long durations and determine all our festivals and all the narrative waypoints of life.

The next steady beat is in some way quieter and much more personal than those. It is the heartbeat.

Dimly overheard but everpresent. Everpresent. That most marvellous muscle sends pressure waves out to your furthest extremities. Your body doesn’t so much as ‘know’ the heartbeat– it is the foundation of all things. New oxygen comes with a rhythm. Your muscles incorporate it into every deed. Your brain swells and shrinks in your skull– do you feel your thoughts quicken and slow with a rhythm? Perhaps?

The heartbeat is no ‘universal’– as if anything is– but considering your little universe it nearly is. Do your thoughts race in time with your heart? Does the world not speed up and race ahead of you when you relax and let it slow?

Top notes: the electric tingle in all your cells, mere existence

Heart notes: the drum of your emotional world, your excitement, your fatigue– manifest!

Bass notes: time itself

The heartbeat defines the pace of time for everything that has it. Could the day be like a heartbeat for a plant? Such speculations are beyond us for now. But pulse-driven creatures like ourselves– you can tell to look at them, if you tried to guess. Pick your nearest animal, look deep in its eyes, look at its gestures and motions and suppose to yourself what its heartbeat might be, what pace it sees the world at. I guarantee you won’t be far off.

There are other bodily rhythms. The stages of development of a body, the menstrual cycle, the period of generations. There are characteristic speeds of twitching, there are brain waves. There is breathing! There is pacing and running! (Breathing– a strange cycle. So forceful on its own and yet nearly within our control! That relationship is a novel to itself.) But this is not a catalogue. I have my players, three big, one small. There are many bit-parts and side characters in this drama– what is the world but a whorl within a whorl, a set of stacked cycles reaching from mere matter out to heaven?

There. We have time. Time enough. We feel ourselves driven onwards by these tiny parcels, normally just at the edge of hearing but rising up in times of drama to a hammering. We wake and see the world, and are reminded in the course of the day of the passage of the month and the year. And if we think of summers or of springs– we can count them somehow, and we are told there are so-and-so many, no more, no less. Or rather less as the case may be but certainly no more.

Is that not enough? Do we lack somehow for stepping stones on our journey from place to place and to the grave? It can be, it really can and often is. But we miss the should and we are curious creatures and life will insist on presenting us with mysteries and puzzles. Why 4 seasons, not three? Why 12 months, not 9 or 15? Nature makes work for idle hands and after the age of agriculture began and slaves and bureaucracy began their millennia of toil idle hands had time to work.

Our metronomes teach us about numbers. Day and night, sun and moon, self and other. Splitting collections– four seasons, four phases of the moon. It is no step at all from there to fractions. Ten fingers to count with so count everything by tens. But why 12? It is a mystery and nature will leave them everywhere. It divides into three and four– two good, honest numbers, numbers even birds can see. Is that explanation enough? Is there something sacred about the act of multiplication itself perhaps? Two by two by three– that is, two sixes, is also twelve.

\(6\cdot10\cdot6\cdot10\cdot2\cdot12\)

\(2\cdot3\cdot2\cdot5\cdot2\cdot3\cdot2\cdot5\cdot2\cdot2\cdot2\cdot3\)

\(2^7\cdot3^3\cdot5^2\)

I don’t now how the scaffolding came about. With twelve echoing in their heads they split the day and night into twelve pieces each. When they noticed those twelve pieces, divided again by twelve and once again. No. I have lost my faith.

Believing that the second is a mechanical mirror of the heartbeat I hoped to understand how they factored the day. But \(4\cdot12^4\) would have our seconds at 0.96 as long as they are– isn’t that just as good, and more beautiful?

Did they really fall in love with 60 first? 60 of all the numbers, 6x101? Is history so contingent, so littered with the artefacts of ancient compromises that we are left with \(2^7\cdot3^3\cdot5^2\) heartbeats in a day, a system imposed almost universally?

[In quickscript: And history is slow and indolent and sticky.]

Well. The best laid plans of. I had hoped at this point in the essay to have understood in a flash of brilliance how the beating of the heart had been built into the foundation of all our everyday activities. But after all the Herz is not the unit of the heart– that’s just a visual pun, another silly accident built into all our endeavours. It is named after a man, a family name.

In any case it is near enough and perhaps there are worse compromises to suffer. The ticking of the clock, that mechanical convenience used to regulate experience, beats with the rhythm of a heart– not the heart mind you, for there is no such thing– but a heart, a common human heart, a heart at rest and at ease with the world, a heart under no duress, no exceptional sickness or stress. A common heart, a heart that most everyone has had for moments, for a beat or two between the quickenings and slowings of our ever-changing duration.

And no doubt it is for the best and might even give us hope that we resist the urge to throw away the oddities we carry with us. Some little quirks of ages past embedded in our lives. The inexplicable way some ancient scribes collected sacred numbers out of nature and assembled them into a scaffolding out of which to build an artifice of shared duration.

Our letters carry marks of many minds. Why not our moments too?

Footnotes

Or 5x12– then you can count by twelve on one hand, and five on the other. Nevertheless.↩︎